Failure modes and effects analysis for management of type 1 diabetes during illness

Hailee Nelson, MD; Sarah D. Corathers, MD; Patrick W. Brady, MD, MSc; Eric Kirkendall, MD, MBI; Richard Ruddy, MD; Tosha Wetterneck, MD, MS; Kathleen E. Walsh, MD, MS

Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) is an approach used to identify how a process can fail, facilitating the development of interventions to reduce the most serious risks. In collaboration with parents of children with type 1 diabetes and diabetes clinic staff, we sought to identify common failures in self-management as well as opportunities to improve ambulatory safety for youth with type 1 diabetes during serious illness.

Hailee Nelson, MD

Abstract

Background: At home, two in five children with chronic disease experience a medication error. Of these, 3.6% are injured due to these errors – the same rate as hospitalized children. The vast majority of care for children with type 1 diabetes (T1D) occurs at home; however, pediatric patient safety research frequently focuses on care delivered in a hospital setting.

Objective: In collaboration with parents of children with T1D and diabetes clinic staff, we sought to identify common failures in self-management and opportunities to improve ambulatory safety for youth with T1D.

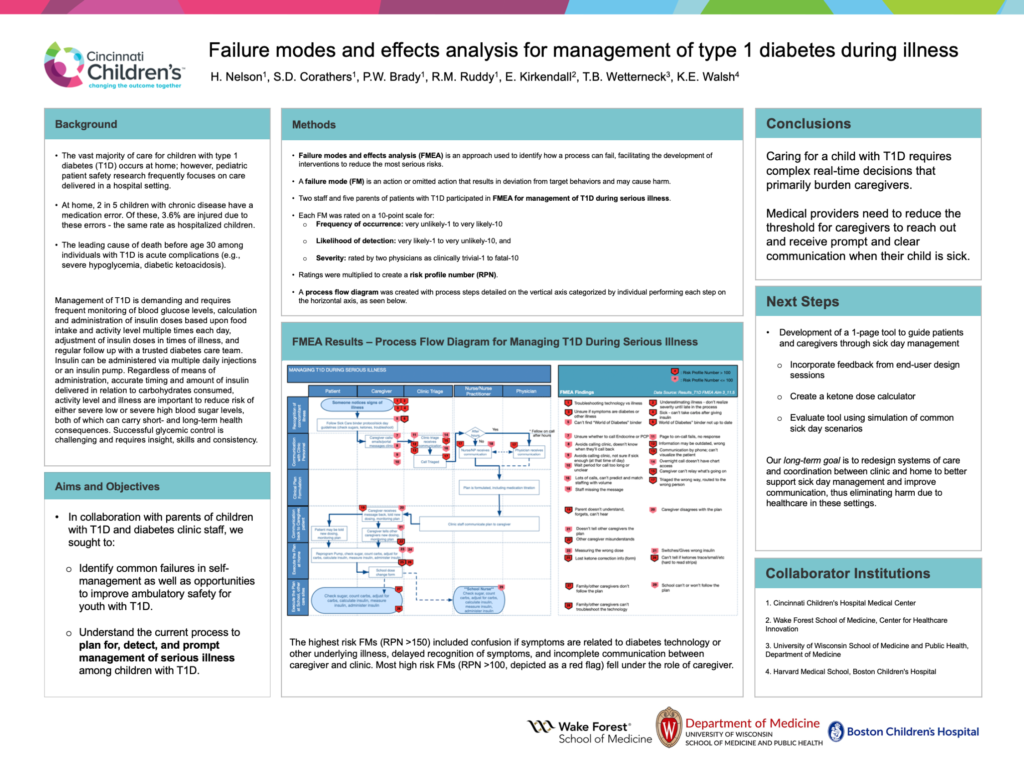

Methods: Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) is an approach used to identify how a process can fail, facilitating the development of interventions to reduce the most serious risks. A failure mode (FM) is an action or omitted action that results in deviation from target behaviors and may cause harm. We performed an FMEA for management of T1D during serious illness. Two staff and five parents participated in FMEA. Participants agreed on process steps categorized by individuals performing each step. Process steps included recognition of concomitant illness, communication with clinic personnel, critical plan formation, communication back to caregiver or patient, and execution of the plan at home or other care sites such as school. Roles included patient, caregiver, clinic triage, nurse or nurse practitioner, and physician. Each FM was rated on 3, 10-point scales: frequency of occurrence (very unlikely to very likely), likelihood of detection (very likely to very unlikely), and severity (rated by two physicians as clinically trivial to fatal). Ratings were multiplied to create a risk profile number (RPN).

Results: The highest risk FMs (RPN ³ 150) included confusion if symptoms are related to diabetes technology or other underlying illness, delayed recognition of symptoms, and incomplete communication between caregiver and clinic. Most high risk FMs fell under the role of caregiver.

Conclusions: Caring for a child with T1D requires complex real-time decisions that primarily burden caregivers. We are developing interventions to redesign systems of care and coordination between clinic and home to better support sick day management and improve communication, thus eliminating harm due to healthcare in these settings.